How independent are African data protection authorities?

In the digital era, in which people generate immense amounts of data that can both empower them and be used to control them, data protection laws are essential. Promisingly, as of June 2023, 36 out of the 55 African countries (that is, 65%) have data protection legislation in place, while 3 have draft bills in progress. Whether these laws are effective, however, depends in large part on whether there is an associated authority tasked with enforcing them.

Of the 36 countries with data protection laws, every one of them establishes a data protection authority (DPA). It is not enough for these authorities to simply exist, however. To effectively execute their mandates, they need to be independent both in terms of how they are structured and how they are funded.

Of the 36 countries that we analysed that have either a law or a draft bill, only 16 (about 46%) have DPAs that are meaningfully independent in structure – that is, they do not exist within or receive instructions from another public body. The remainder are either explicitly not independently structured, or their structure remains unclear; undermining their ability to hold public power to account.

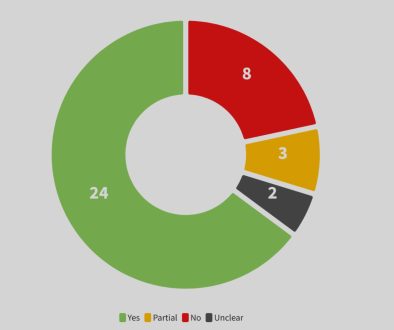

Structural independence is not the only kind that matters. It is also important that DPAs have some degree of financial independence. On this front, the picture is slightly more complicated. 24 of the 36 countries (66%) have DPAs which receive funding from the state budget or a related legislative body. While this may place constraint on the DPA’s operation by opening up space for political interference, it might also be considered important for providing the DPA with consistent and relatively predictable funding.

It may also be important for DPAs to be able to receive external funding or generate their own revenue as well. 22 countries (61%) have DPAs able to do this, while the situation is unclear in 13 countries. Again, the ability to receive external funding does not guarantee independence, but having a path to sustainability that does not depend on the state can be an important safeguard against undue influence.

Finally, it is interesting to look at whether there are adequate protections in place to guard against the undue removal of the heads of DPAs. The data reveals a split into rough thirds, with 11 countries having such protections, 11 lacking them, and 14 being ambiguous. The substantial ambiguity here across multiple factors suggests the need for greater clarity in law.

Without independent data authorities, even the best data protection laws will be practically inert. As the African continent is rapidly developing data protection infrastructure, it is vital that policymakers, advocates, and citizens alike push for clearer laws, greater autonomy, and transparent funding structures for DPAs. This is a vital step toward a future where African citizens are empowered by and benefit from the developments of the digital era.